‘I read the news like a book.’

Therapeutic. That’s how Natalia Karpenko describes the conversation we have with her about the war in her native Ukraine. Natalia managed to evacuate her seventy-two-year-old mother from Kherson, in the south of the country, just in time. Russian troops began their offensive there on the first day of their full-scale invasion and still have the city in their grip. Natalia’s eyes light up when she adds that literature helped her with the evacuation of her mother. A moment later she jumps to her feet and fetches a children’s book she recently translated, to show that we don’t differ so very much from each other.

Some small stories stood out, details that to me were a sign that this escalation was coming.Natalia Karpenko

You say literature helped you to get your mother to safety?

'I’d been following the news from Ukraine and Russia closely for months, because there was menace in the air. I read the news almost like a book. Some small stories stood out, details that to me were a sign that this escalation was coming. It seemed just as if an author was building the tension in a novel. For example, Putin hurriedly brought his yacht, which was moored in Germany for renovation, back to Russia. During military training, temporary bridges were built outside the training grounds. With small anecdotes like that, I started to fill in the sequel myself. It happened spontaneously, probably a quirk of my profession.'

'I shared my panic with my sister, who lives in Germany, and with my mother. At first my mum wasn’t inclined to leave. Nobody wanted to believe that Russia really would attack, even though the conflict had been going on for years. Fortunately she gave up resisting just in time. She took the last train from Kherson to Lviv. When she got there, tens of thousands of people were waiting along with her for a chance to cross the border into Poland. It was late February, so it was cold, and she was going to have to wait for days on end. I couldn’t do that to my mother. Luckily I was able to turn to my network and within a few hours she was on a bus heading for Poland.'

'Meanwhile I’d travelled by plane to Kraków, where I was able to stay with the brother of a Polish friend. He took a day off to drive hundreds of kilometres with me to pick up my mother. On the motorway gantries, which normally give traffic information, Polish solidarity with Ukraine was announced in big letters. It was an extraordinary experience, sad but at the same time beautiful. The willingness to help that surfaces in a crisis situation is special.'

How are the two of you doing now?

'My mother would like nothing better than to go home, but that’s not possible at the moment. She feels uprooted, but we’re also relieved. Kherson has been taken by Russia and closed off from the world. Nothing and nobody is allowed in or out. So there’s a shortage of food, medicine and medical care. Imagine if she was still there now! The evening after my mother left, the trains were stopped and the day after that the railway lines and crucial roads were blown up, to make it more difficult for the Russian troops. She escaped from those horrors just in time.'

I get regular reports from Constantin, a Ukrainian friend who is now defending Chernihiv. He’s hopeful. But I think that’s the only way to be.Natalia Karpenko

How are you experiencing the war?

'I follow the news closely. I also get regular reports from Constantin, a Ukrainian friend who has been in the army since 2014, when he volunteered to go and fight in the east of our country. Constantin is now defending his own city of Chernihiv in the north. He’s hopeful. But I think that’s the only way to be.'

'His wife and two children, aged fifteen and seventeen, have also fled. They left for their holiday home in the Ukrainian countryside a few weeks ago, because they no longer felt safe. Just after they left, their apartment building was hit. Constantin told me that you could see the other side of the street through the hole left by the rocket. So the family didn’t go back, instead they crossed the border westwards like so many others, via Hungary. Now they’re in a reception centre in Bruges and the children are already going to school. I visited them recently and it struck me how restless they are. Their mental agitation expresses itself in an inability to sit still. It’s heartrending. I see the same at the European school where I teach. Two Ukrainian boys arrived there, and when I talk to them it’s as if an air raid alarm might go off at any moment. My hope for them, and for all refugees, is that they find serenity and that beautiful things can develop again, such as new friendships that can last for ever.'

Are there big differences between our two cultures?

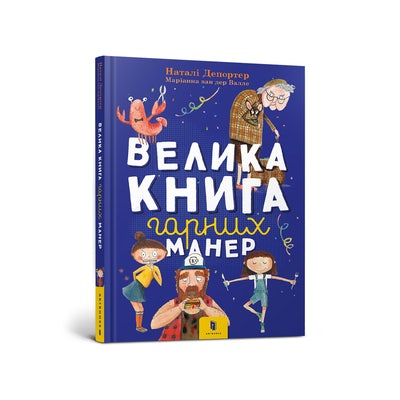

'We’re very similar. The translation of ‘The Big Book of Good Manners’ (written by Nathalie Depoorter and published in 2019 by Clavis), in which etiquette is explained to children, gave me that insight. Both the publisher and I thought we might have to adjust a passage here or there because of differences in cultural codes. In the end, we didn’t come upon a single instance of that. I don’t think there could be better evidence of how similar we are.

But there will of course always be cultural differences, and literature has a part to play then. Books can create connections, open eyes. The Ukrainian translation of ‘The Big Book of Good Manners’ was well received, incidentally. Several Ukrainian public bodies decided to buy the book for their libraries.'

Natalia Karpenko’s first translation, of the short story ‘Bloemen’ (Flowers) by Hugo Claus, was published in 2003 in a Ukrainian magazine for translated literature. Since then she has translated work in various genres, including ‘The Sorrow of Belgium’ by Hugo Claus, a selection of children’s stories from ‘The Best Dutch Sagas and Legends’ and the poem ‘Het schrijverke' (The Whirligig Beetle) by Guido Gezelle.

How can you help?

The Ukrainian Book Institute, supported by the Federation of European Publishers, is appealing to the generosity of the book world and introducing various ways in which you can help Ukrainian refugee children to get hold of books. So that they can remain children by playing, learning and reading.