“The subjects for tough crime stories are here for the taking.”

What’s special about the Flemish crime novel? Journalists Linda Asselbergs and John Vervoort are well disposed towards the genre and follow new developments closely. John has recently joined Flanders Literature’s advisory committee for fiction, while Linda was a member for several years. Both are also on the jury of the Knack Hercule Poirot Prize, awarded annually for the most thrilling Flemish crime novel.

Linda: “The Flemish crime novel is a frequently practised genre. There aren’t an awful lot of Flemings, but every year we receive more than fifty submissions for the prize. I find that remarkable. Many Flemings feel called to write a thriller.”

John: “They’re eagerly read here, too. Of course every Fleming will at some point be keen to read an exciting book set in, say, New York, but we also like stories that take place in our part of the world. Every Flemish city has a writer and a series to match, from Yves Pierreux in Knokke through Toni Coppers in Antwerp to the late Pieter Aspe in Bruges. The creation of atmosphere is therefore an important aspect. Characters who go for a beer on the Dageraadplaats in Antwerp, for instance. A writer needs to make time for that."

That’s unarguably a bonus for the local reader, but does it also appeal to an international readership?

Linda: “Yes! You see a lot of local colour in a crime novel. If you read Flemish thrillers, you get to know Flanders. Or Brussels. When I was a teenager, I started reading Swedish thrillers. The first time I went to Stockholm, I had the feeling I’d already walked its streets.”

John: “But of course we also have crime writers whose novels cross national borders. Jan van der Cruysse for example. Or Benny Baudewyns, whose ‘Buchinsky Incident’ won the Knack Hercule Poirot Prize last year. With the fictional conquest of Brussels by the Russians at the end of the Second World War, that book has a highly ambitious plot.”

Linda: “The books that are set in Flanders aren’t exactly cosy either. Patrick Conrad writes with great nostalgia about Antwerp nightlife and the arts scene of the 1970s – a milieu he knows extremely well – but most of his stories are rooted in current events.”

What international tradition does the Flemish thriller fit into?

John: “Our crime writers have grafted themselves onto the Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon tradition. Think classic crime story centred on a tormented police officer. The kind that likes to sit in a bar, who’s in trouble with his superiors and unhappily married. I don’t know many books about police detectives who’re not struggling with a drinking problem, have a good relationship with their boss and never cheat on their wives.”

What sets us apart, then?

John: “A thriller is more than a tough crime story. In a thriller you can say a lot about a society and its problems. Jef Geeraerts started off that tradition here. It may sound odd, but in Flanders we’re in a good position in that regard. The subjects are here for the taking. The drugs mafia, the migrant issue, trafficking in women ... It’s the same in Brussels, where European and national politics come together and the whole place is crawling with spies and lobbyists.”

Linda: “Things happen here that seem as if they’ve come straight out of a crime story. Conservative members of the European Parliament getting caught at a sex party, for instance. The truth is sometimes more absurd than fiction.”

John: “Flanders – and by extension Belgium – has a fertile history when it comes to historical crime novels: the war, collaboration ... Documents concerning the Nijvel Gang or the Dutroux case can be a source of inspiration for crime writers. And it’s only a matter of time before there’s a book about paedophilia in the Catholic Church.”

You see a lot of local colour in a crime novel. If you read Flemish thrillers, you get to know Flanders. Or Brussels.Linda Asselbergs

international trends

You’ve both been following Flemish crime novels for quite a while now. What evolution have you seen the genre go through?

John: “There have been several. Although you can’t look at those evolutions separately from international trends. First of all, it’s become far more difficult in a technical sense to write a crime story. Just take the drugs mafia. It’s no simple matter to understand the form it takes. Especially when it involves cybercrime, like Sky ECC. And a crime writer today has to take account of the fact that you can hardly walk down the street any longer without being filmed. If you set a break-in in Antwerp, then you’re stuck with the reality of camera images. They make it harder for an author to come up with a credible plot.”

Linda: “Just you try disappearing without trace ... It’s no longer possible. (She laughs.)”

John: “I also have the feeling that the dividing line between real literature and crime literature – which I regard as artificial, by the way – is increasingly thin. Thrillers have actually been becoming more literary since the 1980s and 1990s, with writers like Henning Mankell and Stieg Larsson. I’ve noticed recently that many literary authors – I’m thinking for example of someone like Gaea Schoeters, with ‘Trophy’ – have started to write exciting stories. It’s as if they’ve recognized the need for a compelling plot. The future of literature doesn’t look rosy, but people still love to read a gripping yarn.”

Linda: “That crime stories are increasingly well written is a positive evolution. In the past I often used to think: that’s a nice idea, but stylistically it’s slapdash. There’s still work to be done, though.”

John: “The genre is getting more professional from various angles. Last year I coached a group of six beginning thriller writers through GENRELAB: Thriller, an initiative by author Dimitri Bontenakel that’s subsidized by Flanders Literature among others. Across four weekends I mentored them, along with writer Johanna Spaey and Dimitri himself, as they wrote a new book. A great initiative. It breaks through the solitude of the writing trade, and then there’s the result of the feedback we gave them. Two of the participants have now secured publishing contracts.”

Are there certain themes that are coming our way?

John: “This year several books have appeared that rewrite history. The ‘Buchinsky Incident’, for example, imagines that the Russians didn’t stop at Berlin but got all the way to Brussels. In ‘Blunt Knife’ by Dieter Rogiers and in ‘Bart, Mediocrity and the Stomach Reduction’ by Peter Thiessen, Belgium is split up.”

Linda: “I remember a year with five books featuring chopped-off hands. That must have been a coincidence, but still you think, ‘How is it possible?’ (She laughs.)”

John: “Explicit horror like that is on the wane, incidentally. There was a time when everything had to be extremely explicit. You’d read the most brutal rape scenes. Crime is dirty, the reader should feel that, but it seems as if it’s been done. Things now tend to be implied instead.”

In which countries might the Flemish crime novel do well?

John: “Since our tradition takes inspiration from the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian tradition – and there’s a lot of competition there – as a publisher I’d focus on southern Europe. The atmosphere of French or Spanish crime stories is very different from ours.”

Documents concerning the Nijvel Gang or the Dutroux case can be a source of inspiration for crime writers. And it’s only a matter of time before there’s a book about paedophilia in the Catholic Church.John Vervoort

five crime books

Shall we look for a moment at five crime books that Flanders Literature is shining the spotlight on this spring? Three women on the list. That’s striking.

Linda: “To me too, because in Flanders there’s a preponderance of male crime writers.”

John: “This list shows there’s great potential in women authors as well.”

Linda: “What really stands out is that some women are seeking out the boundaries of the genre.”

You mean ‘Shadowland’ by Sarah Meuleman?

Linda: “Yes. It’s really a psychological novel in which someone disappears and there’s a tragic accident. But it’s mainly about a parent-child relationship – between writer Saul and his daughter Grace – and about the relationship between Grace and her sister. ‘Shadowland’ is an extremely good book, but it’s borderline as a crime novel.”

John: “A crime doesn’t make a book a crime novel. If it did, then ‘Macbeth’ would be the greatest crime novel ever written.”

What do you think of ‘Joséphine’ by Anne-Laure Van Neer, in which a group of elderly people have promised to help each other should they want to end their lives?

Linda: “It pleases me greatly. Elderly people don’t often appear in crime novels, unless they’re murdered. In this book a group of resilient retirees take matters into their own hands. They’ve created a garden of poisonous plants, so that they can help each other if they get to a point when they no longer want to go on living.”

John: “Despite the dark and socially relevant subject, ‘Joséphine’ is a very funny book. There’s nothing easy about that. There aren’t many authors who combine crime and humour. You often end up with a cynical view of the world. ‘Joséphine’ is simply funny. It reminds me of ‘The Thursday Murder Club’ by Richard Osman, in which four elderly people solve crimes.”

Hilde Vandermeeren (with ‘The Scorpion’s Head’) is the third woman on the list.

John: “Hilde is very talented. She had a bit of experience already as a children’s book writer, but her first crime story was an immediate hit. She understands the genre. She also writes the most traditional crime novels of the three.”

Linda: “The idea for her first thriller – about a person who can’t recognize faces – was extremely original from the start. You can do something with a detail like that. The character was in a lift with someone but didn’t know whether they should be fearful or not. I thought that was a brilliant invention. And she managed to make it convincing, too.”

John: “In 'The Scorpion’s Head’ there’s an interesting starting point as well. A woman is accused of trying to murder her young son, but she doesn’t remember anything.”

Then there’s ‘Sacrifice’ by Toni Coppers. Back in 2022 you awarded Toni a prize for his oeuvre as a whole.

John: “Toni is the leading man of Flemish crime writers. He’s the true successor to Jef Geeraerts and Pieter Aspe. It’s sometimes forgotten that writing thrillers is a craft. Well, Tony is an extremely good craftsman.”

Linda: “Giving Toni the oeuvre prize perhaps means we no longer need to nominate him every year and can give other authors a chance. Because he really is the best crime writer we have in Flanders. There’s no getting around it.”

John: “‘Sacrifice’ is part of his second series featuring detective Alex Berger. Toni’s wife Annick Lambert is the co-author of the new series, and the psychology and the interaction between the characters benefit from that. It’s precisely because the characters are so interesting that the series gets more and more thrilling. Alex Berger has now lost his wife, during the attacks in Paris.”

Linda: “Although I really love his Liese Meerhout series too. Liese Meerhout and Michel Masson feel almost like friends, I’ve got to know them so well over the years.”

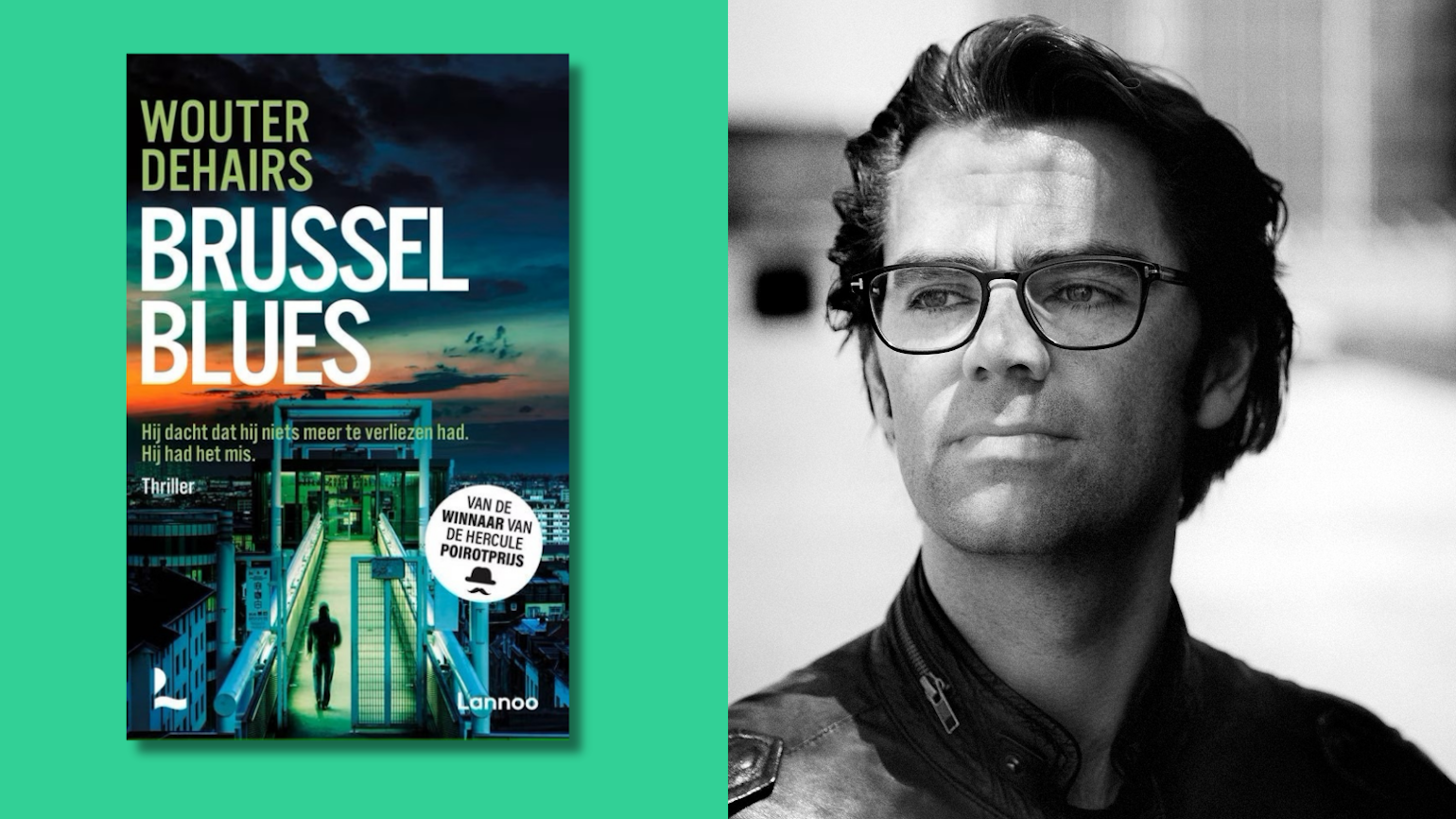

Finally there’s ‘Brussels Blues’ by Wouter Dehairs. What did you think of that?

Linda: “‘Brussels Blues’ is a fantastic book. Wouter plays with the clichés of the genre. Just take the name of the central character, Keller Brik. So macho. Wouter was planning to have Keller killed at the end of this book, but fortunately he decided to carry on with him. His sidekick Gwen Van Meer is based on Lisbeth Salander. Gwen is a strong woman, who looks a little bizarre and has been through all kinds of things. That works. You don’t have to invent the hot water from the start every time.”

John: “Here Brussels truly becomes the ‘hellhole’ that Trump described. It’s hardly an advertisement for Brussels as a city, but the way Wouter portrays the atmosphere is brilliant. He’s understood extremely well what you can do with a big city like Brussels. And his writing is reasonably hardboiled: a touch cynical and very physical. Of an international standard. I think we can expect a lot from him yet.”