Nonfiction in Flanders: a relatively new genre

Flanders is currently experiencing a real nonfiction boom: more nonfiction titles are being published than ever before, more nonfiction is being read than fiction, and many people now regard the genre as literature.

Oral history, research and travel

The history of nonfiction still largely has to be written but, in his acclaimed history of literature, Hugo Brems, professor of Dutch literature, notes a striking trend in literature written in Dutch. While, in the past, travel accounts written by literary authors were often considered a less important part of their oeuvre, around the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, ‘the tide began to turn and the Netherlands and Flanders were inundated with travel stories ranging from literature, essay, report and article to glorified travel guide.’ This, though, was how the genre of nonfiction entered literature. The merging of journalistic account, oral history and local research underlies the oeuvre of the three best-known nonfiction authors in Flanders: Lieve Joris, Chris De Stoop and David Van Reybrouck.

Lieve Joris has grown into one of our most widely read, most respected and frequently translated travel authors.

Lieve Joris has travelled mainly to Africa, the Middle East and China, returning with books in which she distilled stories from the conversations she had with people in those countries, painting a skilful picture of the problems with which these countries were struggling. She has grown into one of our most widely read, most respected and frequently translated travel authors.

Chris De Stoop uses investigative journalism as a starting point, presenting problems such as trafficking in women, suicide bombing and the negative consequences of globalised agricultural policies for small family businesses in his most recent and thus far most personal book This Is My Farm.

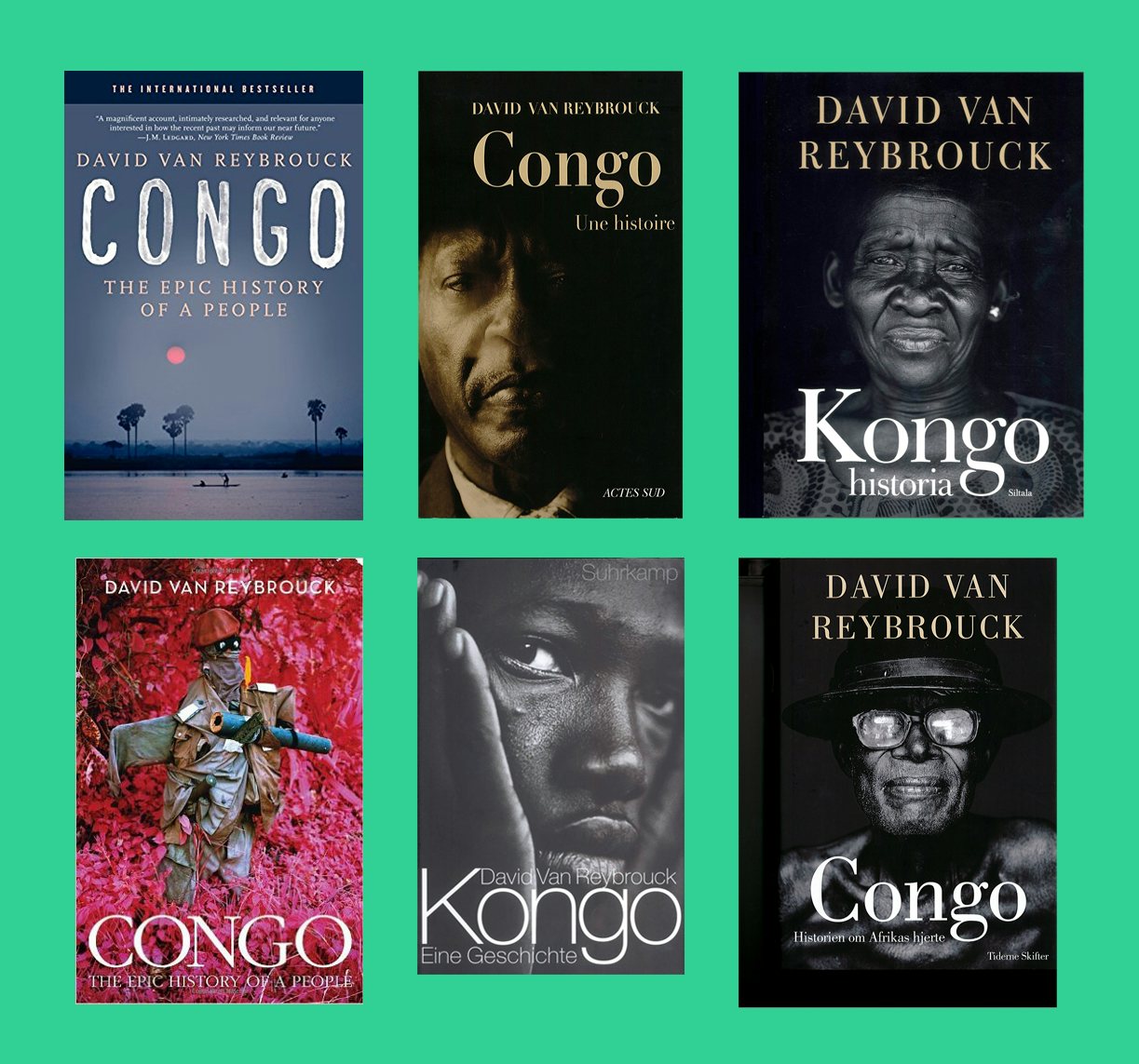

David Van Reybrouck, finally, has had huge success, including internationally, with Congo. A History, his history of that country, based on oral transmission. He combined research, conversation and reporting to create a particularly effective style of historiography. He has also focused on the political situation in Belgium, which has resulted in the books 'A Plea for Populism' and Against Elections, which appeal to a wide audience and have also received interest abroad.

The literary essay is still alive

With these latter books, he is in line with another trend that can be seen within the genre: the literary essay is still a key element of nonfiction. Stefan Hertmans, who recently broke through at an international level with his novels, is a literary author who has long been writing essays on cultural, literary and philosophical themes. Books such as Dubious Matters and The Mobilisation of Arcadia are typical examples of this elaboration on the literary essay, while in his collection Intercities he looked in the direction of travel stories.

The literary essay is still a key element of nonfiction.

Literary subjects also continue to be part of the genre. Geert Buelens, also a poet and academic, has written a book about how European poets dealt with the First World War, while, in Rebellious Rhythms, Matthijs de Ridder looked at the interaction between jazz and literature. Another author who first found his way into literature as a poet, Bernard Dewulf, has had two collections of essays published, 'Small Days' and 'Late Days'. These books are based on the detailed observations that he plucks out of the banality of everyday life and links with philosophical reflections to create essays. It is interesting to note, though, that when 'Small Days' won the literary Libris Prize, the award was not perceived as a huge breakthrough for nonfiction as a genre.

This was, however, the case when Mark Schaevers was lauded for his biography of Felix Nussbaum. Thanks in part to Flanders Literature’s support for biographies and the efforts of a number of publishers, the genre of the biography has experienced an unprecedented boom. When Organ Man went on to win a major literary award, the media considered this not only a prize for a gifted author but also recognition for nonfiction as a literary genre. Biographies of Leopold I, James Ensor, Pieter Bruegel and Beethoven have all been published, and also of Brussels in the Belle Epoque.

The number of academically trained authors who are able to express an interesting subject in a responsible, enthusiastic and clear way is steadily growing. Flanders Literature’s subsidy for nonfiction authors encourages original work in this genre. A number of publishing houses in Flanders, such as Lannoo and Polis, have also made nonfiction a focal point of their programmes. These facts support the idea that nonfiction will remain a rapidly expanding literary genre in Flanders. An example of an author building a new oeuvre is Francophile Bart Van Loo, who continues to publish fascinating books on French subjects.

Non-fiction from academics

In the past decade, nonfiction in Flanders has been characterised by a wide variety and diversity of subjects and authors. Nonfiction titles from every possible academic domain taught at Flemish universities are currently being published, aimed at the general public. One of the inspirations for this development was the success of psychoanalyst Paul Verhaeghe, who reached a wide audience with his Love in a Time of Loneliness, a reworking of a title previously brought out by an academic publisher. In the wake of this success, similar reflections by psychiatrist Dirk De Wachter have been published. Philosophers such as Maarten Boudry, Thomas Decreus, Ignaas Devisch and Jan Verplaetse know how to make their philosophical and political subjects appealing to a wider audience, filling the gap left by Patricia De Martelaere’s early death. Readers with an interest in economics may also find Paul De Grauwe to their liking, while those with socio-political leanings may enjoy Luc Huyse and Rik Coolsaet.