Master storytellers in pictures and words

Flanders, the northern part of the already very modestly sized country of Belgium, may be a small region, but when it comes to literature we can be proud: we punch above our weight. This is also true when it comes to our literature for children large and small. With an artistic tradition that goes back hundreds of years, which they constantly renew and translate into their own style, Flemish illustrators are absolutely world class. And with their precision, their powers of suggestion, their humour and their gift for depicting complex characters, Flemish authors for children and young adults are certainly a match for our illustrators.

Since its inception in 2000, Flanders Literature has always made literature for children and young adults a key part of its programme. Both authors and illustrators make ample use of the opportunity to apply for work grants that buy them the time they need to make books. Flanders Literature is also a regular fixture at all the major book fairs, where we enthusiastically promote top-quality Flemish literature from all genres. We are very proud that in recent years we have facilitated the production of over 500 translations of Flemish books for children and young adults with our translation grants.

Illustration art

But then, we have so much talent in Flanders. Particularly when it comes to illustration, Flanders has a disproportionate number of very strong players. There are several reasons for this strength: for example, Flanders has a number of training programmes where illustration is truly considered an art, with extremely talented tutors such as Gerda Dendooven, Carll Cneut, Klaas Verplancke and Kristien Aertssen. We have publishers, such as De Eenhoorn, Lannoo and the Dutch Querido, who trust their illustrators, giving them a great deal of freedom, and actively go in search of new talent. But there are also less obvious roots for this phenomenon: Flanders has long been a land of passionate storytellers, in words and pictures. The pictorial narrative art of medieval miniatures, majestic tapestries, the Flemish Primitives and later masters is continued today by Ingrid Godon, Benjamin Leroy, Tom Schamp and many, many others.

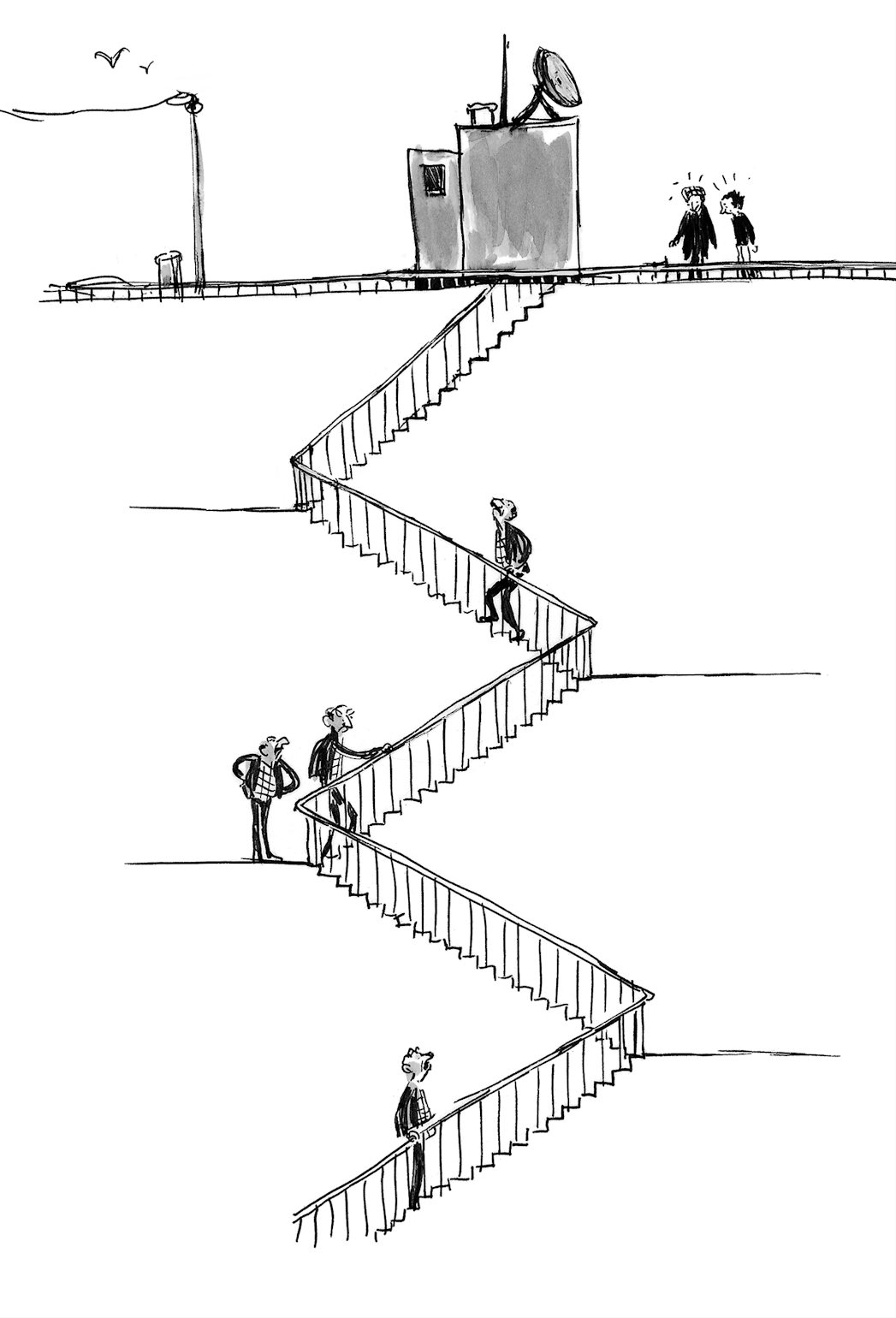

All of these artists work in the line of this tradition, using their own signature styles. Like their illustrious predecessors, they do not limit themselves to supplying the obligatory picture to match the words. They have stories all of their own to tell, and they often do so in a bold and experimental style, allowing their drawings and paintings to add a surprising dimension to the text. The landscape of Flemish illustration is incredibly diverse: from Kaatje Vermeire’s sensitive collages to Isabelle Vandenabeele’s rugged woodcuts, from Carll Cneut’s minutely detailed paintings to Pieter Gaudesaboos, who creates everything digitally. Then there is Sabien Clement, with her typically elongated figures, and Sebastiaan Van Doninck, with his exuberant style full of dynamism. Peter Goes specialises in large drawings packed with details, while Leo Timmers creates cartoonish gouache characters by the dozen. With newcomers like Anton Van Hertbruggen, Alain Verster and Mattias De Leeuw, we can be sure that this succession of top illustrators will not come to an end any time soon.

Taking young readers seriously

And if that makes it sound as if we have only talented illustrators in Flanders, then please read on. Because we can pride ourselves on more than our fair share of great writers too. In the mid-1990s, Bart Moeyaert and Anne Provoost paved the way for literature for younger readers to be taken seriously. This begins with picture books: the multi-talented Peter Verhelst wrote the words for The Secret of the Nightingale’s Throat, for example, and Elvis Peeters shows that literature for the very youngest readers can also contain poetry, with the rhythmic Running. Books for young independent readers, such as the hugely popular duo Fox and Hare (by Sylvia Vanden Heede and Thé Tjong-Khing) and the cheeky Job and his friend the Pigeon (by Evelien De Vlieger and Noëlle Smit) have a style all of their own and a great sense of humour. In his novels, Jef Aerts addresses a middle-grade audience in his vibrant and slightly dreamlike style. Michael De Cock and Judith Vanistendael, in their Rosie and Moussa series, sketch a warm and realistic picture of a budding friendship and life in a big city.

Excellent historical novels

For a slightly older audience, there are plenty of excellent historical novels to be found in Flanders. With a Sword in My Hand is an exciting story about the life of a medieval noblewoman, while Papinette shows us how servants lived in 16th-century Antwerp, and I Think It Was Love presents Paris in the 18th century through the eyes of a foundling who turns out to be a son of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. More recent history, too, in particular the two world wars, has been a fruitful source of inspiration. Els Beerten’s magnum opus We All Want Heaven shows that the line between good and bad is not always clear in wartime and that sometimes it simply shifts. The Dog Eaters takes place far from the front, during the winter famine of 1917, and in The Girl and the Soldier Ann De Bode has created serene pictures to accompany Aline Sax’s small and intimate story.

Subtle tension and unspoken emotions

For anyone who is looking for unique voices, Flanders is the right place.

Of course, there are also a great many wonderful novels that are not set in the distant past. Bart Moeyaert’s stories are never situated within a specific time frame. His books Bare Hands, The Milky Way and It’s Love We Don’t Understand are gems packed with subtle tension and unspoken emotions, depicted in short, vivid sentences. Jan De Leeuw shows his narrative and stylistic diversity in Frozen Rooms, Fifteen Wild Summers and the dystopian Babel. Do Van Ranst sketches a place in the middle of nowhere in My Father Says That We Save Lives, and in Anne Provoost’s atmospheric Falling the past functions primarily as a millstone around the necks of the young characters.

The message is clear: for anyone who is looking for unique voices, Flanders is the right place. Flemish writers stand out because of their use of language and their style, and particularly – and this also applies to the illustrators – for their courage to deviate from the norm. They are non-conformist, moving freely and choosing their own paths, guided by the principle that reading or looking at a book should be first and foremost a unique, creative experience.